Combing through Rubble in Idlib (Khaled Akacha)

By Jeremy Hodge

Executive Summary

The December 08, 2024 overthrow of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad in Syria and subsequent decisions by the Trump administration to lift sanctions on the country’s new government has opened up an array of investment opportunities in key sectors that had been shut off to foreign firms since the 2011 outbreak of the country’s civil war.

Though the country lacks significant oil and gas reserves, since the early 2000s Syria’s geography has made it an attractive location for the construction of oil and gas pipelines linking Middle East reserves to Europe that could serve as alternatives to Russian energy.

Russia’s 2015 intervention in Syria’s civil war was in part motivated to prevent construction of these pipelines. That said, the overthrow of Assad brings new prospects to revive old proposals to link reserves in Israel, Egypt, Qatar and Iraq to European markets. Already, it appears that US firms may be poised to reap the benefits of this new energy regime.

The removal of Assad has similarly opened up Syria to potentially join the India-Middle-East-Europe Corridor (IMEC), a proposed rail transport route that aims to facilitate the transport of products manufactured in India to EU markets.

Lastly, Syria possesses the world’s third largest phosphate reserves, which if brought onto the market could significantly increase world supply of phosphate fertilizer and help address issues of food insecurity and rising food prices in the EU and worldwide.

Pipelines

On June 30, 2025, the Trump administration issued Executive Order 14312 “Providing for the Revocation of Syria Sanctions” that effectively removed all sanctions on the government in Damascus for the first time in decades.

The decision came just over two months after a momentous announcement delivered by President Trump on May 13 at an investment forum in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, declaring an end to Syria’s 13-year sanctions regime, saying the time had come for the country to “move forward” and that Syria deserved a “chance at greatness”.

However, the Trump administration’s decision will likely come with strings attached, in particular conditions that the new Syrian government give American companies priority to lead reconstruction efforts in the country, which after 13-years of civil war is estimated to cost upwards of $400bn.

Prior to the overthrow of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad on December 08, 2024, Russia exploited its leverage over the regime to coerce Syria’s parliament to grant nearly exclusive rights to Russian companies to lead these reconstruction efforts, which Moscow hoped would be paid for by the international community and western states.

Now, after Assad’s overthrow, it appears the United States may have usurped this role, as reports emerged as early as late May that US and Syrian officials had begun talks for American firms to lead a new initiative to rebuild Syria’s oil and gas sector, significantly damaged after 13 years of civil war.

The tentative plan would include the creation of a Syrian-US joint venture, a sovereign energy wealth fund and two unnamed entities to administer assets and oil revenues, both of which would be listed on the New York or NASDAQ exchanges. As part of the plan, American and other western countries would be given priority to rebuild Syria’s existing oil refineries and pipelines and build new unspecified energy export facilities.

So far, American businessman Jonathan Bass, CEO of Argent LNG and Russell Freeman from HKN Energy have appeared at the forefront of negotiations with Syria’s new government to potentially lead implementation of the plan, which would eventually include oil majors such as ExxonMobil, Chevron, Total, Shell, and others.

Though unconfirmed, funding for the project is expected to come from the Gulf states, in particular Saudi Arabia which shortly after Trump’s May 13 visit to Riyadh pledged $600bn in investments that would directly benefit American firms.

The proposed deal resembles others put forth by the Trump administration with both Ukraine and Congo, in which American firms would gain exclusive rights to mine rare earth mineral deposits in both countries in exchange for US security guarantees against Russia and the Rwandan-backed M23 rebel group, respectively.

The US-Syria deal appears aimed from the latter’s perspective at securing American support against Israel, which launched nearly 1,000 airstrikes in Syria since the December 08, 2024 overthrow of President Bashar al-Assad. Already, since Trump announced the removal of sanctions on May 13, 2025, Israel has ended its air campaign and openly called for a peace deal with Syria’s new leadership.

However rather than gain access to mineral or oil and gas deposits in Syria —which are limited— in exchange for helping to end Israel’s air campaign in the country the US will likely seek long-term ownership rights for American firms over Syria’s pipeline networks, which carry significant geostrategic value in worldwide energy markets.

Prior to the outbreak of Syria’s 2011 civil war, Syria’s geography made it an attractive location for investment in new oil and gas pipelines, 4 of which were proposed in the early 2000s that would have passed through the country to deliver energy to Europe from Egypt, Qatar, Iraq and Iran.

These projects were accompanied by similar proposals to link untapped reserves in Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan and Nigeria to Europe through alternative routes.

The proposals were part of a push by the United States to reduce Europe’s dependence on Russian gas, which by the year 2000 made up 74% of EU gas imports and had already been identified by NATO planners as a dangerous source of leverage that Moscow could wield over European member states.

As a result, throughout the 2000s Russia took steps to either sabotage implementation of these proposals or ensure that Russian firms built and maintained ownership over new pipelines, in which case Moscow could arbitrarily shut off the energy flows passing through sections that it owned, preserving its leverage over the EU.

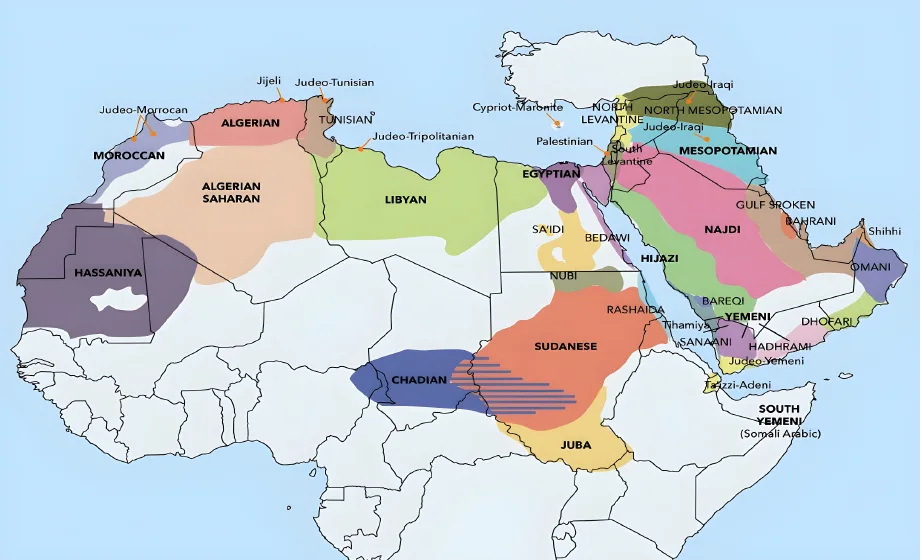

Of the four proposals that would pass through Syria, the Iranian and Iraqi pipelines intended to reach Europe via Syria’s Mediterranean coast, while the Qatari and Egyptian lines would pass through Jordan and Syria before connecting to the Turkish TANAP network that connects to the EU.

By 2010, the first five legs of the Egyptian pipeline —known as the Arab Gas Pipeline— were built, including the 4th, Syrian leg, which was constructed by Stroytransgaz, owned by Russian oligarch Gennady Timchenko, however Syria’s 2011 civil war prevented construction of the sixth and final section. In 2009 Russia pressured Assad to veto the Qatari pipeline despite support from Total and ExxonMobil for the project.

The outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011 similarly delayed both the Iraqi and Iranian pipelines, known as the “Kirkuk-Banias” and the “Islamic Gas” pipelines.

However the passage on July 14, 2015 of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) between Iran and the US, China, France, Russia, the UK, Germany and the EU —which aimed to lift sanctions on Tehran in exchange for an end to its nuclear program— revived the possibility that the Islamic Gas Pipeline could be built.

Throughout 2015, the EU’s European Energy Union openly considered and proposed investing in Iran’s Islamic Gas Pipeline as a means of weaning the bloc off of Russian energy in the aftermath of Moscow’s March 2014 invasion of Crimea.

As a result, Russia’s September 2015 intervention in Syria in support of Assad against the country’s rebel movement occurred in part to monitor Iran’s actions in the country, which deployed tens of thousands of its soldiers and Shi’a proxy fighters to Syria to defend the regime.

In the event that Iran used those troops to outmaneuver Moscow and become the primary security guarantor for the Assad regime, it could compel the latter to open up Syrian territory for construction of the Islamic Gas Pipeline.

As a result, over the next 3 years Russia deployed 4,000 troops to Syria and significant air power —which Iran lacked— that proved indispensable in recapturing significant swaths of territory for Assad from both ISIS and moderate Syrian rebels.

By late 2017, Moscow exploited this leverage over Assad to ensure a near total monopoly for Russian firms in the future building and reconstruction of all Syrian energy infrastructure to prevent rival suppliers from using the country to access the EU.

Today, it appears that the United States may have usurped the role that Moscow sought to acquire for itself, granting Washington further leverage over the EU’s energy sector, which has steadily grown since Russia’s February 24, 2022 invasion of Ukraine, with US LNG already making up 48% of the bloc’s total LNG imports by Q3 2023.

Qatar —which supplies 14% of the EU’s LNG imports— will likely be the second beneficiary of the new energy regime in Syria, as the country’s new government may likely revive the Qatari-Turkey pipeline that Assad vetoed in 2009. Already, just two days after Assad’s overthrow on December 10, 2024, Turkish Energy Minister Alpraslan Bayraktar suggested as such, claiming talks to revive the project were already being considered.

IMEC Corridor: New Syrian Route

In addition to energy infrastructure, Syria’s geography will also likely make it an attractive additional leg to the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC). Originally proposed in September 2023, the IMEC intends to deliver Indian goods to Europe via the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Israel via a unified rail and maritime transport line.

While India, the UAE and Jordan all maintain formal and close ties to Israel, Saudi Arabia —whose large landmass makes up the majority of the proposed rail-line— still does not. Saudi Arabia’s participation in IMEC alongside Israel likely stemmed from the lack of an alternative route at the time to access the Mediterranean, while its proposed normalization with Israel was similarly motivated by a need to counter Iran’s influence in Iraq, Syria and Lebanon.

However the removal of Assad along with Riyadh’s close ties to the new Syrian government will likely push some IMEC nations to consider Syria as an additional if not alternative final leg of the project and reduce Saudi Arabia’s incentive to pursue normalization with Israel.

Already, Jordan and Saudi Arabia have quickly reached agreements with Syria to remove all or most customs on products exported between all three countries. For Saudi Arabia in particular, Israel’s unpopular war in the Gaza Strip has made normalization along with broader economic integration less palatable domestically.

In order to be successful, all of the above-mentioned projects will require a significant reconstruction of existing infrastructure that has been damaged over the course of Syria’s 13-year civil war. Should Syria be included in IMEC or converted into a land-maritime export route for Indian or other goods enroute to Europe, the country’s rail network and ports will also not only need to be rebuilt but also significantly expanded.

Already, foreign firms have rushed to secure contracts in Syria towards this end, with Syria’s General Authority for Land and Sea Ports announcing a $800m MOU on May 15, 2025 with UAE based DP World to redevelop and expand the Tartus Port and associated logistics zones. Syria’s other large port in Latakia will similarly by expanded following a $230m 4-year investment pledge made May 01, 2025 by the French CMA-CGM to operate the port, expand its pier and deepen its surrounding basin.

Phosphate

However, perhaps the most lucrative investments for foreign firms in Syria will occur in the country’s largely untapped phosphate sector. Though its oil and gas reserves are limited, Syria has the third largest phosphate reserves in the world with 1.8bn tons. In 2010, Syria’s total phosphate production reached 3.6m tons, 1.2m of which was exported to the EU, making up 10%-15% of the EU’s total imports.

In addition to the size of its reserves, Syrian phosphate is uniquely competitive as a fertilizer as it contains low levels of cadmium —40mg/kg— a deadly carcinogen whose use is highly regulated in the EU, with significantly lower levels than Moroccan phosphate, traditionally Europe’s largest supplier. Syrian phosphate also contains 300 grams per cubic tons of radioactive-depleted uranium, higher than the 200 grams per cubic ton world average, making it a useful component in nuclear energy.

After 2017, both Russia and Iran jointly extracted Syrian phosphate, the latter for use in its nuclear program and the former in an attempt to secure a larger share of the EU’s fertilizer market, which Moscow had served as the second largest supplier of after Morocco in the 2010s. However, with the overthrow of Assad, new nations can now gain access to these reserves which can be repurposed for other uses.

Already, Saudi Arabia may have an advantage, as in November 2022 the Saudi Seven Wells for Phosphate Investment LLC firm was granted rights alongside Russia and Iran to extract phosphate following a brief attempt by Gulf states to pursue normalization with Assad. Whether the country’s new authorities will honor this contract remains to be seen, however in this and other critical sectors, the international race for influence within Syria has already begun.

Conclusion

- The United States and Qatar are already the first and second largest suppliers of European LNG, helping the bloc reduce its reliance on Russian energy. The opening up of Syrian territory to new regional pipeline projects in partnership with American firms along with prospects for a revival of a Qatari-Turkish pipeline passing through Syria will further solidify both countries’ influence over the European energy sector.

- The overthrow of Assad may bring Syria into the India-Middle-East-Europe-Corridor (IMEC) project, providing a potential alternative route to access the Mediterranean. If accomplished, Saudi Arabia in particular may have less incentive to normalize ties with Israel, particularly following the latter’s defeat of Iranian proxies including Hezbollah and Hamas throughout the region.

- Syria has the world’s third largest phosphate reserves which are also of high quality and purity, with low levels of cadmium and high levels of depleted uranium, making Syrian phosphate particularly attractive in EU fertilizer markets and for various nuclear energy programs worldwide.

Jeremy Hodge is a Research Fellow at New America and at Arizona State University’s Future Security Initiative, where he leads field research teams tracking the recruitment and patronage networks of ISIS, Al-Qa’ida and Iranian backed militias. Hodge has covered the Middle East as an investigative journalist since 2012 and been nominated for awards by the Overseas Press Club and Foreign Press Association of London, writing for Foreign Policy, Foreign Affairs, War on the Rocks, Africa Confidential and other outlets.