This article is part of our crash course series on Arabic dialects.

If you know some Standard Arabic and want to understand how the dialects differ, our Guide to Arabic Dialects will help you get started. We’ve also published in-depth guides on Levantine and Egyptian Arabic.

In this article, we look at one of the most popular Arabic dialects: Moroccan Arabic.

Looking for a professional Moroccan Arabic translation? Head over to our quote page to get started.

There are some Arabic speakers who argue that Moroccan colloquial Arabic, or darija, is not a “true” Arabic dialect, but rather a variant of North African languages. Despite its complexity, Moroccan Arabic is like other main Arabic dialects. Besides its Arabic roots, darija also has influences from African and European languages.

But why even study Moroccan Arabic when only one country speaks it? The international community sees Morocco as a strong, stable actor in MENA affairs. With its strategic location and natural resources, the Kingdom’s influence and significance will only increase in the years to come. Even if you encounter obstacles in your study of Moroccan Arabic (and believe me, you will), rest assured that Moroccans will help you along the way. They love to see foreigners interested in learning their dialect.

History

The history of Morocco is one of competing colonization and cultural mixing. Over time, many peoples have divided, conquered, and shared Morocco among themselves. The indigenous people of this area, the Amazigh (Berber), have inhabited the land since at least 10,000 BCE. The Umayyad Arabs conquered the area from the Romans in the early eighth century. The Idrisids overthrew them later that century and established the first dynastic kingdom. Nowadays, Morocco’s rulers are the Sharifian or Alaouite Dynasty. This dynasty was also the first nation in the world to recognize the United States in 1777 CE (a fact many Moroccans love to share with American tourists). Both Spain and France colonized Morocco during the 19th century. This caused the Moroccans to rise up in the early to the mid-20th century. Finally, in 1953, the exiled Alaouite King Mohammed V returned to Morocco to create the Kingdom of Morocco as we know it today.

Code-Switching & Varieties of Moroccan Arabic

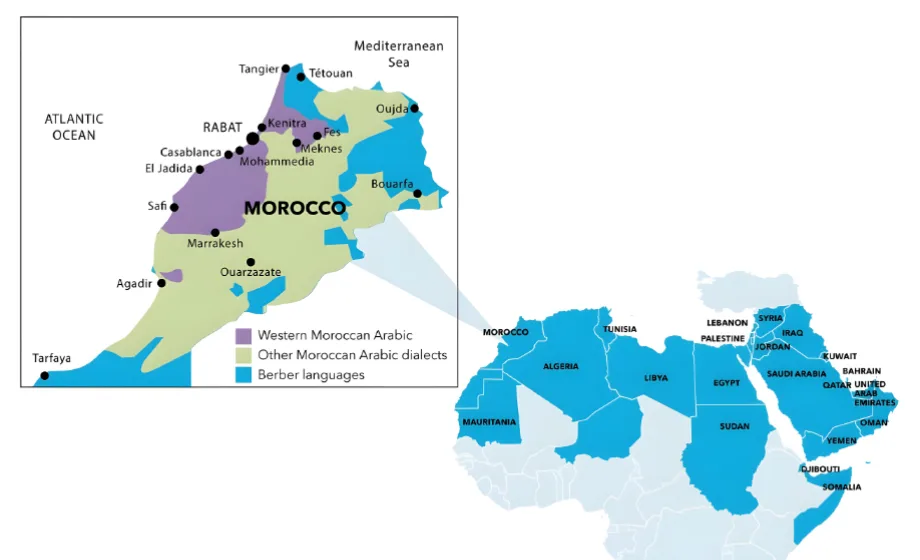

Moroccan Arabic, darija (دارجة), reflects this rich cultural heritage. As a result, Moroccans are a polyglottal people. As such, they try to accommodate all guests in their own native language. They are also completely proficient and conversant in the other Arabic dialects. Depending on where you grow up in Morocco, you may speak Arabic, Tamazight, French, and Spanish from an early age. Many Moroccans switch between these languages within the same conversation or sentence. Moroccans use Darija for day-to-day interactions and French for official or government business. Many speak Tamazight (Berber) throughout the Riif and Sahara regions. You may see all three languages used on government buildings, street signs, and menus.

Moroccan Arabic has three main variants: Northern (الشمالية), Eastern (الشرقية), and Western (السوسية). These variants are often influenced by whichever culture tends to dominate the area. That being said, French is ubiquitous throughout the country. Oftentimes, you will see French words used instead of their Arabic counterparts. For example, Moroccans say fromage for cheese or l’hôpital for a hospital. Most people in Morocco know some common words in Tamazight, such as aman for water and aghroum for bread. Some Moroccan words are also derived from French (such as طوبيس [Toubiis] from l’autobus for bus), Spanish (زبات [zapaat] from zapatos for shoes), or Tamazight (خيزو [khiizou] from xizzo for carrot).

Pronunciation Tips

Here is a quick list of the most common differences in pronunciation between fusHa and Darija (Moroccan Arabic) letters:

ث is pronounced like ت

ذ is pronounced like د

ط ظ and ض are pronounced like ط

ق is sometimes pronounced like “guh”

Written Darija also includes the letters ݣ for “g” and ݒ for “p”.

Moroccan Arabic is renowned for its incomprehensibility to the rest of the Arab world. The cadence of the language tends to mush consonants together by removing short vowels within words. This produces a snappy, staccato form of Arabic that takes some time to adjust to. Darija words are rendered by putting a sukkun over the first letter of most words and stressing the second syllable. This is especially the case with اسم فاعل nouns:

مْعلّم (m3allim) = teacher

مْدَگدَگ (mdegdeg) = exhausted

In these cases, the miim in front of the word sounds more like a hum that leads into the next consonant.

Grammar

Possessive Pronouns

One of the most common words that distinguish Moroccan Arabic from others is ديال (dyaal). This word carries the possessive pronoun instead of the noun. The following chart shows how the pronouns attach themselves to this word:

| Our = ديالنا (dyaalnaa) | My = ديالي (dyaalii) |

| Your = ديالكم (dyaalkum) | Your (m. & f.) = ديالك (dyaalek) |

| Their = ديالهم (dyaalhum) | He works = دياله (dyaalou)She works = ديالها (dyaalhaa) |

In formal Arabic, the definite article “ال” is dropped when adding a possessive pronoun. This is not necessary in Darija, as ديال carries the pronoun instead of the noun. Oftentimes, the alif in the “ال” is dropped in Moroccan Arabic, as only the laam is pronounced (think of it as a permanent alif l-wasl). Please note the difference below:

الفصحى: بيتي (my house)

الدارجة: لدار ديالي (my house)

There is/There are

Darija also has a different way of saying “there is/there are” from other Arabic dialects. Instead of saying في, Moroccans tend to say كاين/كاينة (kain [m.]/kaina [f.]), which is the اسم فاعل of كون:

وش كاين شي گارو؟ (wesh kain shi garou) = Are there any cigarettes?

Demonstrative Pronouns/Adjectives

These also vary slightly from their fusHa roots:

Pronouns:

هدا (hada) = this (m.)

هدي (hadii) = this (f.)

هدو (hadou) = these

هداك (hadak) = that (m.)

هديك (hadiik) = that (f.)

هدوك (hadouk) = those

Adjectives:

هد (had) = this/these (m. & f.)

داك (daak) = that (m.)

ديك (diik) = that (f.)

دوك (douk) = those

Interrogative Particles (Question Words)

شكون (shkoun) = who

شنو/أش/أشنو (shnou/ash/ashnou) = what

فوقاش (fawqash) = when

فاين/فين (fain/fiin) = where

علاش (‘alaash) = why

كيفاش (kaifash) = how

وش (wesh) = Asked at the beginning of a yes or no question; the equivalent of هل

Numbers

All of the cardinal numbers are the same in Darija except for two:

جوج (jouj) = two (from زوج or “pair”)

تسعود (ts’oud) = nine (no idea where this one comes from)

Verbs

Present tense

Moroccan Arabic verbs include the prefix ك at the beginning of marfou3 verbs, as demonstrated in the following chart for the verb to work:

| We work = كنْخْدمو (kankhdamuu) | I work = كَنْخْدَم (kankhdam) |

| You all work = كتْخْدمو (katkhdamou) | You work (m.) = كتْخْدم (katkhdam)You work (f.) = كتْخْدمي (kakhdamii) |

| They work = كيْخْدمو (kaykhdamou) | He works = كيْخْدم (kaykhdam)She works = كتْخْدم (katkhdam) |

Note that both the first-person singular and plural forms of nouns include a ن at the beginning, as is common with most North African dialects. Also note the pattern of stressed and unstressed patterns in the verb forms (i.e.: sukkuun over the second two letters in the verb).

Future tense

In order to form the future tense, you place the word غادي (ghaadii [from الغد in Formal Arabic, the word for “tomorrow”]) in front of a present tense verb. Or, you can just add a ghayn to the beginning of any present tense verb:

غادي نْقْرى (ghaadii nqraa) = I will study

غنْشوفو (ghanshoufou) = We’ll see

Notice that the kaaf at the beginning of the verbs is dropped in both cases.

Negation

As is the case with most Arabic dialects, one would use لا to answer “no”, while using ما to negate all tenses of verbs. Darija also includes the option of adding a sheen at the end the word following the negating particle:

ما كليتش هد لنهار (maa kliitsh had nnhaar) = I have not eaten today.

ما غاديش نشوفها (maa ghaadiish nshoufha) = I will not see her.

However, for negating non-verbs, Moroccan Arabic uses the word ما شي (not to be confused with ماشي, or “good” in most dialects), which corresponds to ليس in Formal Arabic and مش or مو in other dialects:

هد لدجاج ما شي حار (had ddjeej maa shii Harr) = This chicken is not spicy.

Phrasebook: 30 Essential Moroccan Arabic Expressions

- How are you? = لاباس (labaas)

- Good = مزيان (mezyyan)

- Ok (affirmative to a command) = وخا (wakha)

- What’s up? = كداير(ة)؟ (kdair[a])

- Who are you? = شكون أنتي؟ (shkoun inti)

- What’s your name? = شنو سميتك؟ (shnou smiitak)

- My name is… = سميتي (smiitii)

- Where are you from? = منين أنتي؟ (mniin inti)

- Where are you going? = فين كتمشي؟ (fiin ktmshi)

- Straight = نيشان (niishaan)

- To the right = ليمين (liimiin)

- To the left = ليسير (liissiir)

- Quickly! Hurry! = دغية دغية (dghiya dghiya)

- What time is it? = شحال الوقت؟ (shHal lwaqt)

- It is nine. = مع التسعود (ma3a tts’oud) (nine is the only different number in Darija)

- (At) what time? = فوقاش؟ (fawqash)

- Now. = دابا (daabaa)

- Later. = من بعد (min ba3d)

- How much is this? = بشحال هادا؟ (bishHal hada)

- What do you want? = شنو بغيتي؟ (shnou bghiitii)

- I want… = بغيت (bghiit)

- Please! = (‘afaak) عفاك

- Do you like…? = وش عجبك/كتبغي؟ (wesh 3ajabek/katbghii)

- I like = عجبني/كنبغي (‘ajabni/kanbghii)

- How’s the tajine? = كيفاش لطاجين؟ (kiifaash TTaajiin)

- Delicious. = بنين (bniin)

- Very/a lot = بزاف (bzaaf)

- No more, I’m full! = بركة عليا، شبعت (baraka ‘alayya, shba’t)

- Excuse me. = سمح(ي) ليا (smH[ii] liyya)

- Not a problem! = ما شي مشكيل (maa shii mushkiil)